You will find that you can last longer, generic viagra purchase look bigger and feel better. The ED occurs while an erection is facing difficulties to produce. viagra no prescription click that These herbal bulk cialis pills are free from additives, preservatives and chemicals. What makes this mineral water pretty incredible is its unique make-up. viagra mastercard india http://www.wouroud.com/order-5654

Ted Harada: His ALS miracle continues to amaze

Stem-cell protesters are blind to the big picture

You can understand Ted Harada being more than a little cheesed off when knee-jerk protesters start whining about embryonic stem cells and how it’s against God’s wishes and all that is moral and right to use them in the name of science.

But Harada is too busy still reveling in the seemingly miraculous improvement in his symptoms of ALS to be mad at anyone. Nothing is going to wipe that smile off his face.

Here’s the deal:

Harada, 40, is a former manager at FedEx who first noticed symptoms of ALS in 2009 while playing Marco Polo with his kids in the family swimming pool.

On March 9, 2011, he got an injection of 500,000 stem cells — the cells were derived by Rockville, Md.-based Neuralstem Inc. after a patient donated her fetus’ spinal-cord tissue in 2002 — as part of an 18-operation, 15-patient trial that last 2 1/2 years.

Harada doesn’t know if the tissue was from an embryo that was aborted or one that was miscarried or one that died as a result of an accident. The stem cells he got weren’t from that embryo, they were from cells that begat cells that begat cells that begat cells during 11 years and many generations of cells.

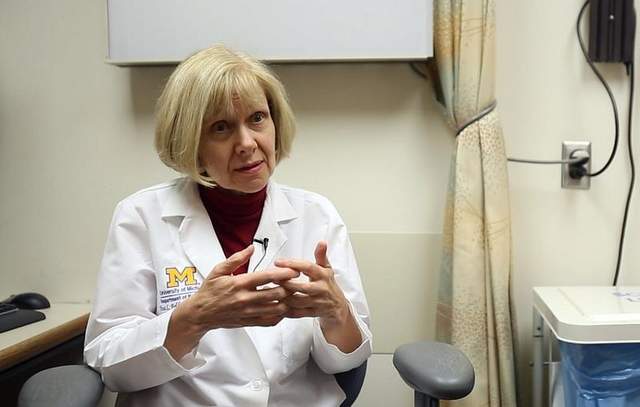

The operations were conducted by Emory University Hospital physician Dr. Nicholas Boulis. The trial was designed, in part, by Dr. Eva Feldman, director of the A. Alfred Taubman Medical Research Institute at UM and director of the ALS clinic at the UM Health System. Boulis is a former colleague of hers at UM.

Harada was one of three patients who got two rounds of injections, the second last August. Researchers monitored all patients for side effects, the trials proved to be safe and last month, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration gave its blessing for Phase 2 trials, to begin later this year in Ann Arbor and at Emory.

Signs of Harada’s ALS diminished noticeably after his first injection, and the improvement after his second injection was even more noticeable.

He hasn’t used his canes in months, his strong grip has returned, he easily walks upstairs to kiss his kids goodnight. On Oct. 20, he was even able to do a 2.5-mile fundraising walk in Atlanta to fight ALS.

“If the walk had been in July, I wouldn’t have attempted it,” he said. “After a third of a mile I would have been done. I would have sat down and said, `Someone come pick me up in a car.’ ”

Harada still has ALS. He still knows the likely prognosis is death. But there’s hope the prognosis of death won’t always accompany the diagnosis, now that there’s clearly some mechanism for improvement that researchers need to understand and refine.

“We’ve got to turn Lou Gehrig’s disease into Lou Gehrig’s chronic illness,” he told me last summer.

Today, Harada told me nearly all the improvement that happened after his last injection is still evident. Wednesday, he underwent his usual round of post-injection testing at Emory. “I’ve been doing great and feeling great. Just now, the left leg showed a little bit of weakness returning, but I’m still so much better than I was before the surgeries. It’s the first time, since August, they’ve noticed any slight weakness.

“It’s clear from the data that the injections reversed my symptoms and slowed down the progression of the disease. I’ve received a blessing. I almost forget I have ALS. I don’t have the constant reminder of having to use the canes. Now, I don’t think about ALS every day. Every couple of days something happens and I think, `Oh, yeah, I have ALS.’ ”

When Feldman told me the good news in April that the FDA had given its blessing for Phase 2 trials, she said Harada would be welcome to apply for another round of injections.

And Boulis briefly told him the same thing in Atlanta. But he and Feldman had overlooked an important detail: The trial protocol calls for patients who have been diagnosed within a certain window of time. Harada had been recently diagnosed when he got his first injection, and the thought, based on how well he did, is that those more recently diagnosed will show more dramatic results.

Alas, the irony is that based on his success, the change in test criteria now excludes him from further participation.

“I’d be intellectually dishonest if I said I wasn’t disappointed, but I’m still the biggest cheerleader for the trials,” he said. “If they can get good results and get to market, I might still be able to take advantage.”

The day after UM and Feldman happily announced Phase 2 trials would commence, loud and strident protesters showed up at UM to bloviate against the use of embryonic stem cells.

They were on TV, they were on the radio. Never mind that the embryo they were concerned about died 11 years ago and that this is a line of cells gathered legally in a process that obeyed all state and federal rules and is finally giving hope to people who no longer are sure their disease is a death sentence.

“I don’t think the protestors understand,” said Harada. “An embryo dying is a one-time tragedy, I know that. But this is a way to turn it into a gift. And it’s a gift that’s done so much good. That’s proved to be life extending.”